A look into how little power branding and trademarks hold in online marketplaces.

Amazon has been the sore-spot of journalism for quite some time now. Amongst various things people could take issue with, we find one key business practice that I’d like to expand on in this blog – the sale of Amazon Essentials products.

For most categories of product, Amazon considers itself the breeding-ground in which companies can arrive with their products, and prove to Amazon whether or not these products will sell.

If it does, it’s often not long before we find Amazon coming forward with an Amazon Essentials product that works remarkably similarly to other products of that type. In fact, it’s a known practice that they work with the same manufacturers of those products.

The impact of Amazon Essentials is simple – everyone else loses out. You’ve shown Amazon the value of the product you’re selling, taken all the risk in making this happen. Then just when you come forward with a viable business Amazon are able to use their power, their clever product placement and the machine-learning algorithms they own to ensure they sell plenty of their own-brand products.

While this is awful, I think it’s important that we stay aware that Amazon aren’t the only ones doing this.

Google is no better

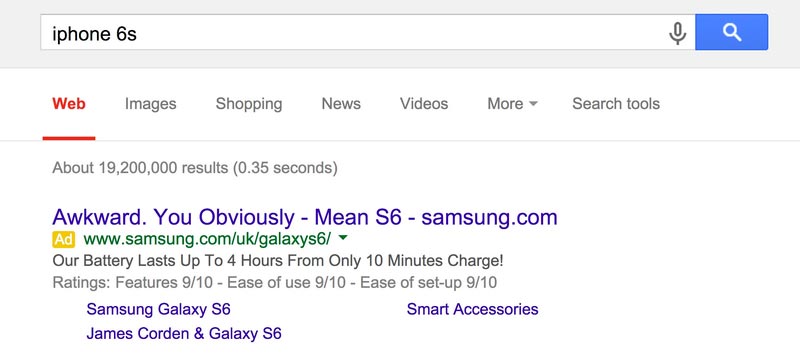

This has been a hugely contentious aspect of how Google Ads works. Let’s say I was Samsung (lucky me!) and had my own range of phones. My biggest competitor is Apple. Google allows me, with absolute freedom, to purchase Ad space on what is clearly a trademarked name.

If someone is searching for ‘iPhone’, they want Apple – not Samsung.

This is incredibly clear before the launch of every iPhone over the last 5 years – the Samsung Ads have become increasingly conversational, mocking and self-aware of where they stand.

Why is it that a competitor of yours could steal potential customers who are specifically trying to look for you? Is this fair?

Taking Tesco as an example

I’ve had the pleasure of working at a Tesco in my teens, and I learnt a fair bit about how they operate in the process.

Most surprisingly (this says a lot) was a time where we’d sent off a pack of Tesco’s Wheat Biscuits (imitation Weetabix) to the manufacturer because they were defective. To my surprise, the response from the manufacturer happened to have Weetabix’s logo at the top of the page.

“What the f—?”, I thought. “Weetabix are selling their own product without their packaging to Tesco, who flog it at a cut-rate? Where’s the profit in that? Why not say ‘no’ and then keep all that sweet, sweet cereal money for yourself?”

There were many things I didn’t quite understand at 18, and the power that marketplaces hold was certainly one of them.

Today…

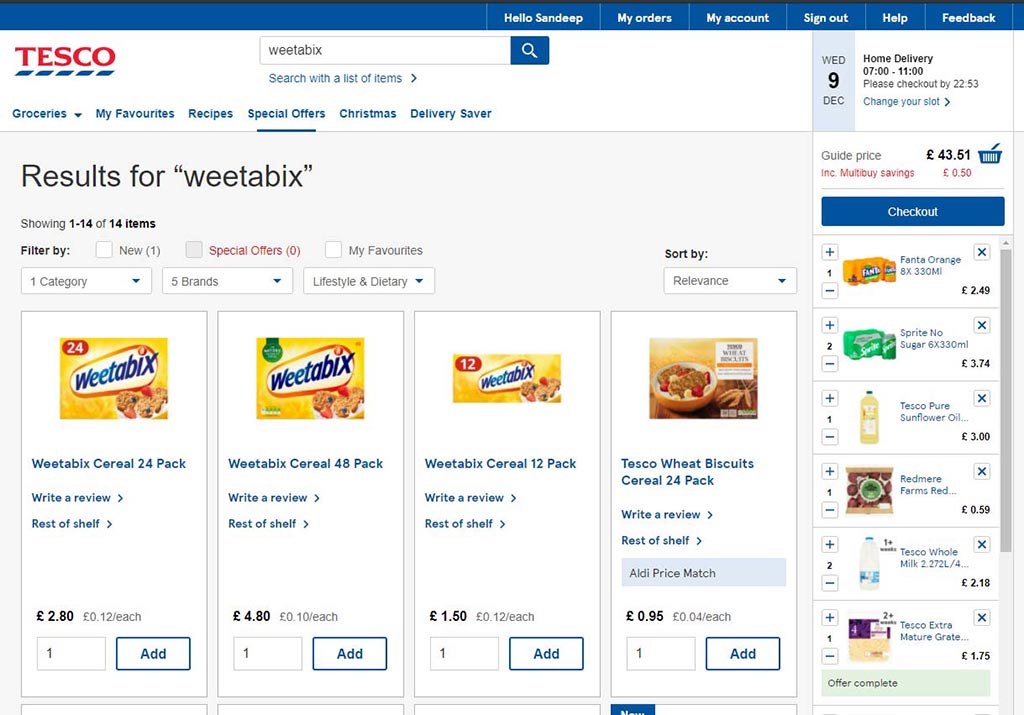

Go to Tesco.com, and search for ‘Weetabix’. On the first row of products, you find a neatly nestled Tesco’s own-brand product.

For context – one product of the 14 on the page is from Tesco, the rest are all Weetabix. And yet Tesco’s own-brand product takes priority over 10 others – roughly 3/4s of their product range.

Is this an anomaly? No. Search for ‘Coca Cola’, and you’ll find 10 of the 24 items on the first page are from Pepsi. Page 2 is scattered with Tesco’s own-brand drinks.

Weirdly, this isn’t consistent, and that makes me even more sceptical. Search ‘Colgate’ for example (something I’ve seen Indians often swap out for ‘toothpaste’). Not one of the 43 products are anything other than products from the Colgate brand.

And it’s no different for 94 products from Cadburys, 31 products from Uncle Bens, anything from Dolmio, Fairy Liquid, Finish Dishwasher Tablets, Pampers, etc. – the list goes on.

Different toilet, same ….

Sure, the scale might not be the same. It might not be as aggressive or deceptive. But it feels like these huge marketplaces are all the same when it matters.

Your trademarks and products don’t mean anything. The marketplace holds two key powers over its products:

- It controls what to show, when

- It can choose to own-brand products from the same manufacturer, and make a decent profit in the process (or run a loss-leader)

So, do your trademarks matter?

I believe they do, and they should. And where people choose to insert themselves ahead of what is clearly a search for your trademark, they should be held to account.